Quality, Quantity, Creativity

There are two competing narratives about the current television landscape. The first is that we’re living through a golden age of scripted shows. From The Sopranos to Transparent, Breaking Bad to The Americans: the art form is at its apogee.

The second narrative is that there’s way too much television - more than 400 scripted shows! - and that consumers are overwhelmed by the glut. John Landgraf, the CEO of FX Networks, recently summarized the problem: "I long ago lost the ability to keep track of every scripted TV series,” he said last month at the Television Critics Association. “But this year, I finally lost the ability to keep track of every programmer who is in the scripted programming business…This is simply too much television.” [Emphasis mine.] Landgraf doesn’t see a golden age – he sees a “content bubble.”

Both of these narratives are true. And they’re both true for a simple reason: when it comes to creativity, high levels of creative output are often a prerequisite for creative success. Put another way, throwing shit at the wall is how you figure out what sticks. More shit, more sticks.

This is a recurring theme of the entertainment business. The Golden Age of Hollywood – a period beginning with The Jazz Singer (1927) and ending with the downfall of the studio system in the 1950s – gave rise to countless classics, from Casablanca to The Searchers. It also led to a surplus of dreck. In the late 1930s, the major studios were releasing nearly 400 movies per year. By 1985, that number had fallen to around 100. It’s no accident that, as Quentin Tarantino points out, the movies of the 80s “sucked.”

The psychological data supports these cultural trends. The classic work in this area has been done by Dean Keith Simonton at UC-Davis. In 1997, after decades spent studying the creative careers of scientists, Simonton proposed the “equal odds rule,” which argues that “the relationship between the number of hits (i.e., creative successes) and the total number of works produced in a given time period is positive, linear, stochastic, and stable.” In other words, the people with the best ideas also have the most ideas. (They also have some of the worst ideas. As Simonton notes, “scientists who publish the most highly cited works also publish the most poorly cited works.”) Here’s Simonton, rattling off some biographical snapshots of geniuses:

"Albert Einstein had around 248 publications to his credit, Charles Darwin had 119, and Sigmund Freud had 330,while Thomas Edison held 1,093 patents—still the record granted to any one person by the U.S. Patent Office. Similarly, Pablo Picasso executed more than 20,000 paintings, drawings, and pieces of sculpture, while Johann Sebastian Bach composed over 1,000 works, enough to require a lifetime of 40-hr weeks for a copyist just to write out the parts by hand."

Simonton’s model was largely theoretical: he tried to find the equations that fit the historical data. But his theories now have some new experimental proof. In a paper published this summer in Frontiers in Psychology, a team of psychologists and neuroscientists at the University of New Mexico extended Simonton’s work in some important ways. The scientists began by giving 246 subjects a version of the Foresight test, in which people are shown a graphic design (say, a zig-zag) and told to “write down as many things as you can that the drawing makes you think of, looks like, reminds you of, or suggests to you.” These answers were then scored by a panel of independent judges on a five-point scale of creativity. In addition, the scientists were given a variety of intelligence and personality tests and put into a brain scanner, where the thickness of the cortex was measured.

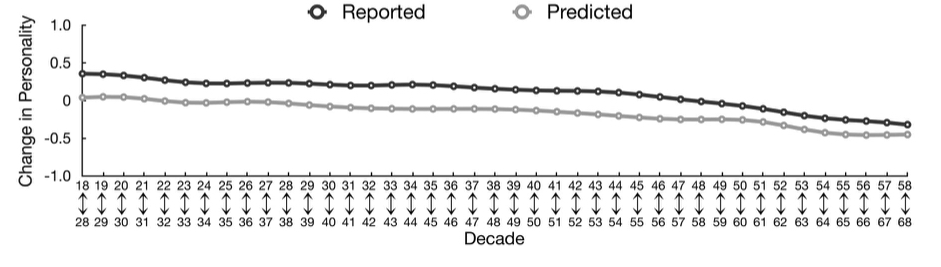

The results were a convincing affirmation of Simonton’s theory: a high ideation rate - throwing shit at the wall - remains an extremely effective creativity strategy. According to the scientists, “the quantity of ideas was related to the judged quality or creativity of ideas to a very high degree,” with a statistical correlation of 0.73. While we might assume that rushing to fill up the page with random thoughts might lead to worse output, the opposite seemed to occur: those who produced more ideas also produced much better ideas. Rex Jung, the lead author on the paper, points out that this “is the first time that this relationship [the equal odds rule] has been demonstrated in a cohort of ‘low creative’ subjects as opposed to the likes of Picasso, Beethoven, or Curie.” You can see the linear relationship in the chart below:

The scientists also looked for correlations between the cortical thickness data and the performance of the subjects. While such results are prone to false positives and Type 1 errors – the brain is a complicated knot – the researchers found that both the quantity and quality of creative ideas were associated with a thicker left frontal pole, a brain area associated with "thinking about one's own future" and "extracting future prospects."

Of course, it’s a long way from riffing on a zig-zag in a lab to producing quality scripted television. Nevertheless, the basic lesson of this research is that expanding the quantity of creative output will also lead to higher quality, just as Simonton predicted. It would be nice (especially for networks) if we could get Breaking Bad without dozens of failed pilots, or if there was a way to greenlight Deadwood without buying into John from Cincinnati. (Call it the David Milch conundrum.) But there is no shortcut; failure is an essential inefficiency. In his writing, Simonton repeatedly compares the creative process to Darwinian evolution, in which every successful adaptation emerges from a litter of dead-end mutations and genetic mistakes. The same dismal logic applies to culture.* The only way to get a golden age is to pay for the glut.

Jung, Rex E., et al. "Quantity yields quality when it comes to creativity: a brain and behavioral test of the equal-odds rule." Frontiers in Psychology (2015).

*Why? Because William Goldman was right: "NOBODY KNOWS ANYTHING. Not one person in the entire motion picture field knows for a certainty what's going to work. Every time out it's a guess..."