The Root of Wisdom: Why Old People Learn Better

In Plato’s Apology, Socrates defines the essence of wisdom. He makes his case by comparison, arguing that wisdom is ultimately an awareness of ignorance. The wise man is not the one who always gets it right. He’s the one who notices when he gets it wrong:

I am wiser than this man, for neither of us appears to know anything great and good; but he fancies he knows something, although he knows nothing; whereas I, as I do not know anything, so I do not fancy I do. In this trifling particular, then, I appear to be wiser than he, because I do not fancy I know what I do not know.

I was thinking of Socrates while reading a new paper in Psychological Science by Janet Metcalfe, Lindsey Casal-Roscum, Arielle Radin and David Friedman. The paper addresses a deeply practical question, which is how the mind changes as it gets older. It’s easy to complain about the lapses of age: the lost keys, the vanished names, the forgotten numbers. But perhaps these shortcomings come with a consolation.

The study focused on how well people learn from their factual errors. The scientists gave 44 young adults (mean age = 24.2 years) and 45 older adults (mean age = 73.7 years) more than 400 hundred general information questions. Subjects were asked, for instance, to name the ancient city with the hanging gardens, or to remember the name of the woman who founded the American Red Cross. After answering each question, they were asked to rate, on a 7-point scale, their “confidence in the correctness of their response.” Then, they were then shown the correct answer. (Babylon, Clara Barton.) This phase of the experiment was done while subjects were fitted with an EEG cap, a device able to measure the waves of electrical activity generated by the brain.

The second part of the experiment consisted of a short retest. The subjects were asked, once again, to answer 20 of their high-confidence errors – questions they thought they got right but actually got wrong – and 20 low-confidence errors, or those questions they always suspected they didn’t know.

The first thing to note is that older adults did a lot better on the test overall. While the young group only got 26 percent of questions correct, the aged subjects got 41 percent. This is to be expected: the mind accumulates facts over time, slowly filling up with stray bits of knowledge.

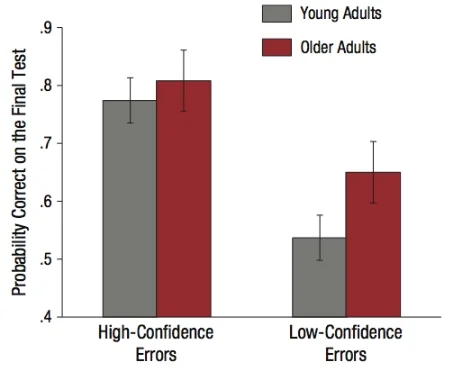

What’s more surprising, however, is how the older adults performed on the retest, after they were given the answers to the questions they got wrong. Although current theory assumes that older adults have a harder time learning new material - their semantic memory has become rigid, or “crystallized” – the scientists found that the older subjects performed much better than younger ones during the second round of questioning. In short, they were far more likely to correct their errors, especially when it came to low-confidence questions:

Why did older adults score so much higher on the retest? The answer is straightforward: they paid more attention to what they got wrong. They were more interested in their ignorance, more likely to notice what they didn’t know. While younger subjects were most focused on their high-confidence errors – those mistakes that catch us by surprise – older subjects were more likely to consider every error, which allowed them to remember more of the corrections. Socrates would be proud.

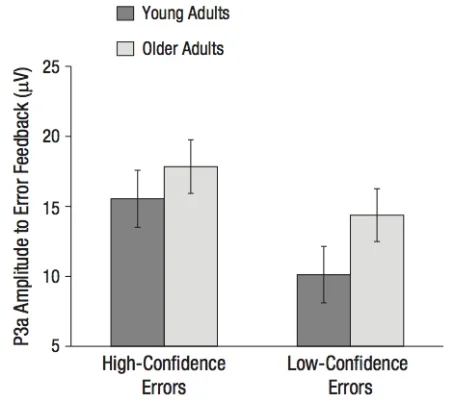

You can see these age-related differences in the EEG data. When older subjects were shown the correct answer in red, they exhibited a much larger P3a amplitude, a signature of brain activity associated with the engagement of attention and the encoding of memory.

Towards the end of their paper, the scientists try to make sense of these results in light of research documenting the shortcomings of the older brain. For instance, previous studies have shown that older adults have a harder time learning new (and incorrect) answers to math problems, remembering arbitrary word pairs, and learning “deviant variations” to well-known fairy tales. Although these results are often used as evidence of our inevitable mental decline – the hippocampus falls apart, etc. – Metcalfe and colleagues speculate that something else is going on, and that older adults are simply “unwilling or unable to recruit their efforts to learn irrelevant mumbo jumbo.” In short, they have less patience for silly lab tasks. However, when senior citizens are given factually correct information to remember – when they are asked to learn the truth – they can rally their attention and memory. The old dog can still learn new tricks. The tricks just have to be worth learning.

Metcalfe, Janet, Lindsey Casal-Roscum, Arielle Radin, and David Friedman. "On Teaching Old Dogs New Tricks." Psychological Science (2015)