How Magicians Make You Stupid

The egg bag magic trick is simple enough. A magician produces an egg and places it in a cloth bag. Then, the magician uses some poor sleight of hand, pretending to hide the egg in his armpit. When the bag is revealed as empty, the audience assumes it knows where the egg really is.

But the egg isn’t there. The armpit was a false solution, distracting the crowd from the real trick: the bag contains a secret compartment. When the magician finally lifts his arm, the audience is impressed by the vanishing. How did he remove the egg from his armpit? It never occurs to them that the egg never left the bag.

Magicians are intuitive psychologists, reverse-engineering the mind and preying on all its weak spots. They build illusions out of our frailties, hiding rabbits in our attentional blind spots and distracting the eyes with hand waves and wands. And while people in the audience might be aware of their perceptual shortcomings – those fingers move so fast! - they are often blind to a crucial cognitive limitation, which allows magicians to keep us from deciphering the trick. In short, magicians know that people tend to to fixate on particular answers (the egg is in the armpit), and thus ignore alternative ones (it’s a trick bag), even when the alternatives are easier to execute.

When it comes to problem-solving, this phenomenon is known as the einstellung effect. (Einstellung is German for “setting” or “attitude.”) First identified by the psychologist Abraham Luchins in the early 1940s, the effect has since been replicated in numerous domains. Consider a study that gave chess experts a series of difficult chess problems, each of which contained two solutions. The players were asked to find the shortest possible way to win. The first solution was obvious and took five moves to execute. The second solution was less familiar, but could be achieved in only three moves. As expected, these expert players found the first solution right away. Unfortunately, most of them then failed to identify the second one, even though it was more efficient. The good answer blinded them to the better one.

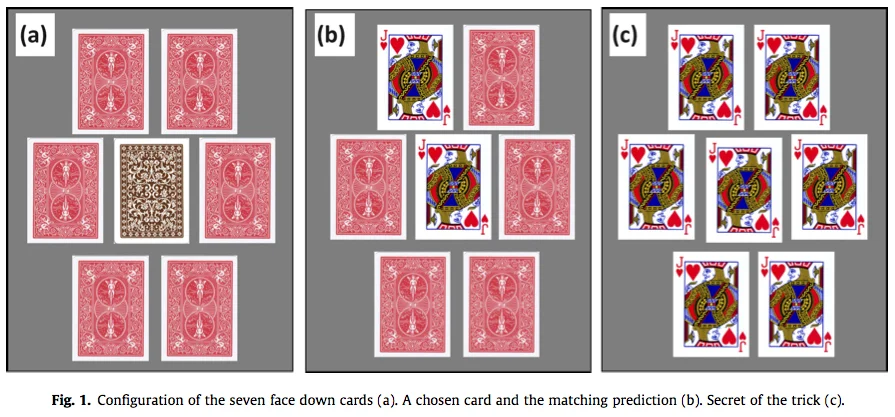

Back to magic tricks. A new paper in Cognition, by Cyril Thomas and Andre Didierjean, extends the reach of the einstellung effect by showing that it limits our problem-solving abilities even when the false solution is unfamiliar and unlikely. Put another way, preposterous explanations can also become mental blocks, preventing us from finding answers that should be obvious. To demonstrate this, the scientists showed 90 students one of three versions of a card trick. The first version went like this: a performer showed the subject a brown-backed card surrounded by six red-backed cards. After randomly touching the back of the red cards, he asked the subject to choose one of the six, which was turned face up. It was a jack of hearts. The magician then flipped over the brown-backed card at the center, which was also a jack of hearts. The experiment concluded with the magician asking the subject to guess the secret of the trick. In this version, 83 percent of subjects quickly figured it out: all of the cards were the same.

The second version featured the same trick, except that the magician slyly introduced a false solution. Before a card was picked, he explained that he was able to influence other people’s choices through physical suggestions. He then touched the back of the red cards, acting as if these touches could sway the subject’s mind. After the trick was complete, these subjects were also asked to identify the secret. However, most of these subjects couldn’t figure it out: only 17 percent of people realized that every card was the jack of hearts. Their confusion persisted even after the magician encouraged them to keep thinking of alternative explanations.

This is a remarkable mental failure. It’s a reminder that our beliefs are not a mirror to the world, but rather bound up with the limits of the human mind. In this particular case, our inability to see the obvious trick seems to be a side-effect of our feeble working memory, which can only focus on a few bits of information at any given moment. (In an email, Thomas notes that it is more “economical to focus on one solution, and to not lose time…searching for a hypothetical alternative one.”) And so we fixate on the most salient answer, even when it makes no sense. As Thomas points out, a similar lapse explains the success of most mind-reading performances: we are so seduced by the false explanation (parapsychology!) that we neglect the obvious trick, which is that the magician gathered personal information about us from Facebook. The performance works because we lack the bandwidth to think of a far more reasonable explanation.

Thomas and Didierjean end their paper with a disturbing thought. “If a complete stranger (the magician) can fix spectators’ minds by convincing them that he/she can control their individual choice with his own gesture,” they write, “to what extent can an authority figure (e.g., policeman) or someone that we trust (e.g., doctors, politicians) fix our mind with unsuitable ideas?” They don’t answer the question, but they don’t need to. Just turn on the news.

Thomas, Cyril, and André Didierjean. "Magicians fix your mind: How unlikely solutions block obvious ones." Cognition 154 (2016): 169-173.